Hine-nui-te-po speaks to me about birth, life and death, about love between man and women, mother and child.

Herstory is multi layered and intersects Whenua, Whakapapa and Tupuna. A personification of Mana Wahine (power of women) as creator and destroyer of life.

Herstory explains the Whangaroa landscape being marked by cosmological and geographical events. How iconic landmarks are named after her body parts as being in, on and of the land.

Herstory as a mirror

Hine nui te po offers me a mirror for my soul to reflect upon.

She symbolises the darkness of the earth’s womb where life germinates and transforms. The dark is not evil but primal and allows for the process of self-reflection to occur.

Herstory embodies feminine and masculine energy that I explore for deeper understanding of my own mauri.

A reminder of my own Atua given weaknesses and strengths to experience in order to function as an integrated whole: that is spiritually, physically, mentally and emotionally unified.

Hine-nui-te-po encourages me to explore for deeper understanding of who I was, who I am and who I am yet to be.

This collection of painting pay homage to her.

Waka-tu-papa-ku o Whangaroa

These waka-tu-papa-ku (bone chests) are the remnants of herstory and echo a unique Whangaroa carving style I use to symbolise the restoration of our cultural art heritage.

These Taonga tuku iho (art of the ancestors) are more then inanimate objects, but living in every sense of the word.

They are revered symbols of cultural identity that connect me to the stories (pu rakau) of my ancestral past, providing a source of content for my creative present to reflect upon.

This collection of waka-tu-papa-ku fill me with a sense of ihi (power), wehi (fear) and wana (awe).

Powerful transformative forces that invite me to experience emotional response.

It is my hope that oneday they will be repatriated to their rightful resting place here in Whangaroa.

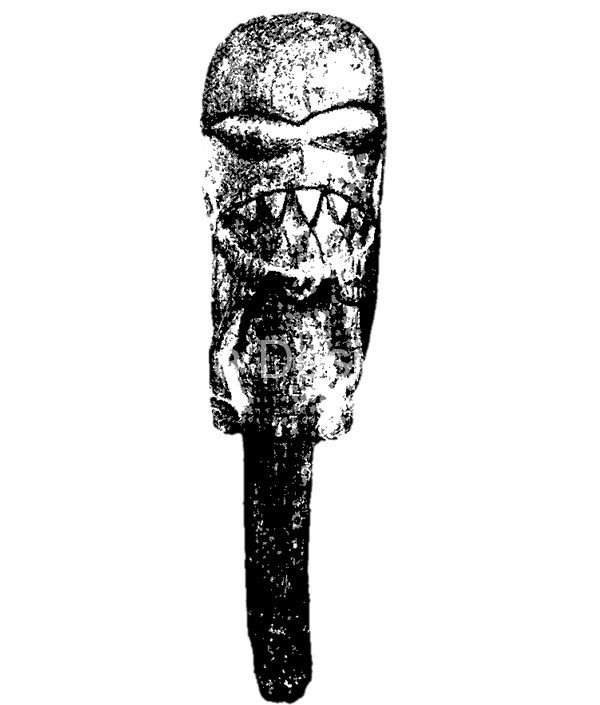

The lid and head of this waka tupapaku are missing, with signs it has been subjected to burning.

Found on a rock platform protruding from a crevice on the slope of Taratara.

Deirdre Brown – Tai Tokerau Whakairo Rakau, Northland Maori Wood Carving

Sold to the Auckland War Memorial Museum by William Saies in 1914, during an exploration of Ohopekako (St Peters), Whangaroa.

Museum records note that the waka tupapaku contained the bones of a small child.

It is unknown how old the carving is, however it is made of Totara and stands 63 cm tall, interior length 24 cm, and interior width 13 cm.

Slide reference: Deirdre Brown – Tai Tokerau Whakairo Rakau, Northland Maori Wood Carving

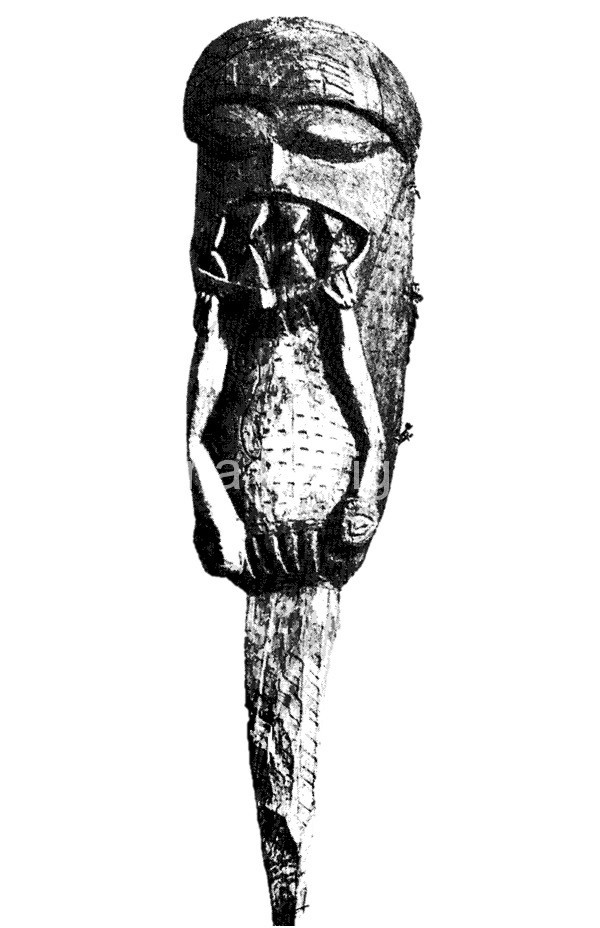

This waka tupapaku was sold to the Auckland War memorial museum by Mr E Spencer in 1913.

Records describe the waka tupapaku as a skull box, made to contain the head of a chief. Its height is 70 cm.

The figure depicted is Hine-nui-te-po, with raised legs and exposed genitals lined with obsidian teeth.

A direct reference to Hine.

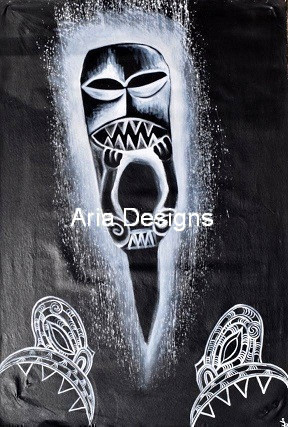

In reverence to the waka-tu-papaku (bone chests) I invoke in her image, a powerful force of nature.

The kowhaiwhai in red represent bloodlines and in white the spiritual umbilical cord that connects us to atua, whenua, whakapapa and whanau. From earth to sky this bloodline is direct and unwavering. It tethers me to past, present and future.

Acrylic paint on loose canvas

2016

Collection of the artist

Māui represented here in lizard form, climbed up the thighs of Hine-nui-te-po while she slept.

The piwaiwaka (fantail) asked, ‘what are you doing’ and Māui told him, ‘I want to return to the womb’ where he was sure he could receive immortality.

The piwaiwaka warned Māui about violating the lores of nature, but Māui continued on his journey.

The Piwaiwaka laughing at the ridiculousness of the situation, woke the sleeping Hine-nui-te-po who demanded to know what Māui was doing.

He told her he wanted to be like the Moon.

She agreed to grant Māui his wish, crushing him with the obsidian teeth in her vagina.

As requested, Māui reappears like the moon in the blood-tides of woman, appearing monthly signalling continuity and the immortality of the people down through the generations.

Acrylic paint on loose canvas

2016

Collection of Seaton Smith

Reference: Leonie Hayden - Decolonise your body! The fascinating history of maori and their periods

2016

In the darkness of her womb is where life germinates, where life begins to transform.

Where human dualities of the spiritual and physical dimensions, heaven and earth, man and woman - are one.

The tohu represented here, the waxing moon, the planet Venus all reference feminine cyclic energy.

The floating kowhai flower signals the mullet are running, and the Kauwau (Black Shag) a metaphor symbolising the world above and the world below.

Hine-nui-te-po is captured in veil, representing both physical and spiritual dimensions.

Acrylic on canvas

2016

Collection of Seaton Smith

Set in volcanic rock she sits at the entranceway to the harbour and echo's a time in herstory when it was known as Te Pokopoko (cervix) of Hine-nui-te-Po. Standing directly across from her also etched in volcanic rock is Te Urenui O Maui (The big penis of Maui).

Iconic sentinels (Kaitiaki)that mark the Whangaroa land and seascape.

Taratara and Maunga Emiemi, are wahi tapu and visually strong icons of Whangaroa, represented here as spiritual anchorstones where the bones of our beloved ancestors restfully watch over us.

The lunar symbolism is built on the belief that life is regenerative as is the three phases of the moon, new, waxing and waning.

The celtic knot acknowledges my Scottish ancestry, although estranged to me, a makeup of my cultural identity none the less, its remnants residing deep down in my bones.

Acrylic on canvas

2018

Collection Mereana Anderson