Cultures collide in black and white to symbolise the deconstruction of our Tikanga and Hapurangatiratanga through colonisation.

This painting by Tupaia in 1769 is the influence for this collection of mahi.

Tupaia was the Tahitian tohunga (priest) who sailed with Captain Cook across the South Pacific as his guide, navigator and translator. Charting and claiming Islands of Polynesia for the British Crown.

Here Tupaia depicts a scene with Joseph Banks the botanist, trading cloth with a Maori chief for Koura (crayfish).

Trade was a key factor in establishing sovereign relationships between Tangata whenua and the British Crown that resulted in the Declaration of Independence of 1835, re-asserted by the Treaty of Waitangi in 1845.

The Waitangi Settlement process: Briefs of evidence

Evidence submitted by Whangaroa claimants for the Waitangi Settlement process of 2016, identifies Crown breaches and the impacts that followed.

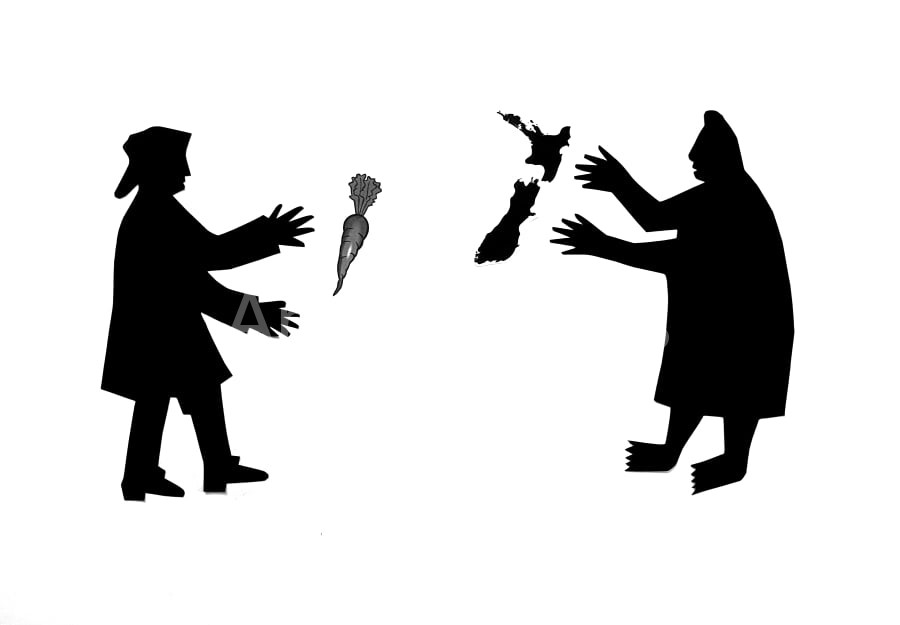

Using silhouettes of the settler and the chief, they are depicted in various forms of trade impacting – Mana Atua, Mana whenua, Mana wahine and Mana tangata.

In black and white a narrative is represented, showing various tools of colonisation to signal the end of the stone age era and the beginning of the iron age era.

During the creative process of this mahi, I became aware that by subverting the tools of colonisation, they become symbols of de-colonisation for the reconstruction of Mana Atua, Mana Whenua, Mana Tangata and Mana Wahine.

Acknowledgement to whanaunga and fellow artist, Frances Goulton for creative collaboration in this mahi toi.

The imagery continues to evolve in present day events, to be adapted into teaching aids for Treaty workshops at schools, marae etc.

List of collages

Con/version

Symbolised here in the form of the cross, is the 'word of god' introduced in 1814 by the RMS – the Royal Missionary Society.

The Maori chief holds a carved wakatupapaku (bone chest) of Hinenuitepo (the great lady of the night) symbolising a matriarchal culture in opposition to the teachings of the missionaries, that elevated one God, God as man.

This impact saw the acceleration of land loss with the church amassing vast areas of land ownership by the 1900's.

It also saw the division between Ira Wahine and Ira Tane, a complimentary, symbiotic relationship by nature, now opposing forces that placed tane as superior and wahine as inferior.

The destruction of Tane

The introduction of iron to a stone age culture resulted in vast areas of ngahere deforested - displacing Tangata whenua for the transplanting of the cow, sheep and horse. Pine forests and other Crown practices detrimental to the environmental health and wealth of Tangata whenua soon followed.

The chief holding the Kauri symbolises the destruction of Tane (atua of the forest) as we see our waterways and foreshore impacted by siltation and erosion.

The Kauri tree also symbolises the felling of our Tinorangatiratanga.

The Kauri tree is a photocopy of a print by one of my favourite Maori artists, Rei Hamon.

Mokai for muskets

Represented here is the introduction of muskets and the 'NZ land wars' that erupted. It comments on the morbid trade of two moko mokai (dried tattooed heads) for one musket as a common form of currency during the 1800's. The head in Maori culture regarded as very tapu was commodified as valuable items of trade by the colonial culture that today are found in collections all over Europe. The use of moko mokai also comment on the intellectual property rights of Tangata whenua, another threat to our cultural identity, packaged by the coloniser as 'cultural capital'.

De - humanisation

This collage comments on the Crowns lust for land for the purpose of mineral extraction. This is a major concern for the Tangata Whenua of Whangaroa faced with the tyranny of mining prospects, not new to us or our tupuna. Here the settler holds a pickaxe, the symbol for mining and the chief with a foetus representing whenua (land), whakapapa (bloodlines) and nga uri (future generations). An example of how the man and womens role in colonial culture is unnaturally reversed.

It symbolises the systematic de-humanisation of our Whenua for Crown profit and the commodification of our Wahine and Rangatahi.

Colonial law thas deeply impacted Tikanga, Hapu Rangatiratanga and Whanaungatanga.

Effectively severing wahine from whenua and whenua from whakapapa.

Assimilation

Here we have the settler who trades the written word, the ink well and quill with the chief who holds the 3 kete of knowledge. Tribal purakau vary, but for Whangaroa, it was Tawhaki , not Tane who brought the baskets of knowledge to the tangata whenua. His name is given to the landmark - Te Ara Tawhaki at Matanehunehu, Whangaroa, and expressed in the following tauraparapa. Matanehunehu is the birthplace of my Tahaawai tupuna Tahaponga, father of Tuhikura, mother of Hongi Hika.

Tauraparapa

Tawhaki ki muri

Tawhaki ki mua

Tawhaki ki Whangaroa

Matanehunehu te teitei o Tawhaki ki te tihi o Manono

Tawhaki ka puawai

The imposition of colonial education taught the debasement of our oral traditions as myth, and the written word of the coloniser as law.

Trauma associated to Te Reo due to violence being inflicted for speaking it at school, is inter-generational.

Our tupuna encouraged English be learnt at school, did not fore see it would be lost from the home.

Shame associated with Matauranga as inferior to settler/western knowledge led to the de-construction of our cultural identity that impacts our psyche today and well into the future.

‘Having no written language of his own, he (Maori) cannot be said to have a history, it is only by shifting his legends and deleting the improbable that we have constructed one for him’.

Naming the other images of Maori in NZ film and television: Martin Blythe, 1994

The carot or the garden

Here the settler holds a carot, a symbol for Crown settlement being offered to Ngapuhi and the chief who holds the map of Aotearoa. A symbol of the garden of which the Treaty promised full and unextinguished rights to.

Ngapuhi have unanimously rejected the Crowns offer, with their sights set firmly on the garden.

Subject or Sovereign

Here the Union Jack is used to represent the subjectification of Tangata whenua, while the United Tribes flag symbolises a sovereign entity. A flag endorsed by King William VI in 1835, to be flown on their sailing ships, that guaranteed free trans-Tasman trading passage. The suppression of this fact by the Crown has impacted on our sovereignty that the Treaty promised to protect.

Stunting our socio-economic development of Tangata whenua evidenced in the negative statistics that plague us today. With this in mind, the question is, how will tangata whenua of today respond to these grievances? How will the Crown honor Te tiriti and redress these injustices.

Only time will tell.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/flags-of-new-zealand/united-tribes-flag